Three days after I de-planed at SeaTac and rode home to peel off sticky, faded desert camo for the last time, I was dispatched by my exotically sexy wife to attend to her mother in the mental ward.

In Texas.

With barely a hug and certainly no kisses under our belts, it seemed early in the reacquaintance process to be leaving the state. Mine not to question why; mine but to salute and execute.

Does that ever go away, that reflex to saddle up and follow orders? My outcomes from it haven’t generally been optimal, but the key in my back never falls out no matter how hard I dance The Chicken to shake it loose.

Down in Houston, my sister-in-law had broken into Shui Ma-Ma’s house. After calling several times, Wen had scaled the garden gate and peered through the sliding glass door to find her mother bleeding out onto the kitchen floor.

Taking a firm grip on the red oak grip of her Japanese vegetable cleaver, Ma had sliced her radial veins wide open at the elbow where their torn edges twitched in trauma, sluicing out her blood fast enough to rapidly depress her brain-bruising blood pressure of 185/123.

She wasn’t messing around.

So I spent a few days at the hospital there. Lily didn’t come along, and I never questioned her about that. The Yellow Rose of Seattle had work to do — responsible corporate work, not puttering around the aisles of a dusty old hardware store, or scribbling notes about a so-called that war nobody cared about. There were markets to build, currencies to trade, the Nisei to track, credit defaults to swap around.

Anyway, it has to be hard, thinking of your own mother that despondent, so I bit my lip and succeeded — at the expense of badly shredded lip linings — not to remind my sleek wife that we never visited my own mother, one state away in Oregon, because lovely Lily thought Mom was “weird” and was given to frequent reiteration that visiting my family stressed her out.

Besides, her Ma and I always got along pretty well — at least after that first visit. That was the time that Ma and her one daughter, two sons and squealing grandson visited our new home in one cackling group, not three months into our marriage.

Clothing was immediately strung all over the house on Lily’s older brother’s insistence that his shirts had to be air-dried, indoors. We did four loads of dishes every day, countless laundry (much of it snot-encrusted toddler duds), and later received a $387.00 water bill in an envelope containing an advisory from the Lake Forest Park Water District to investigate for plumbing leaks.

Silent as a Guatemalan domestic, I chauffeured the gibbering clan around the Northwest in my four wheel-drive, club cab company truck. We toured from Mount Rainier to the Space Needle to Stevens Pass, where my erstwhile nephew shrieked in outrage and hunched rigidly into a fetal position after we’d paid up front for his ski rental and a private lesson. At the next pay period, I reimbursed my company for $636.00 of gasoline charges without even attempting an explanation.

Three days into this family bonding gala, Lily decided she’d had enough and left the building. Realizing that I no longer spoke the native language of my house (press “one” for Mandarin, “two” for Taiwanese), I sought refuge in the garage, first carving a wooden spoon for Ma, then pounding away with a thick rawhide mallet to chop out dovetails for a set of pine book boxes Lily had ordered. Maybe they would come right. Maybe they would make her happy. Maybe she wouldn’t just . . . well, leave.

Poking her head out the door, Ma frowned and told me I was making too much noise, so I grabbed a book and went back in to sit quietly on the sofa, grimly fixated on the anticipated relief of getting up early and bolting for a job site in Lewis County, 96 miles to the south.

The Chinese can narrow their eyes very effectively, leaving nothing but a black hole to nowhere as you fall into a rabbit hole of bottomless, angry pupils. Sitting on the love seat across from me, Ma pinned me with a basilisk stare evidently inherited from her daughter.

“So,” she said, “this happen . . . often?”

She’d personally experienced the fall of Chiang Kai-Shek and later gathered her family to flee Nicaragua as refugees. I couldn’t bullshit Ma. I closed the paperback and spread my hands, palms up.

“Ma, I don’t even know where she is. This is all new to me.”

“You have temper, too. Sometime, not only what you say. Sometime how you look.

“You give The Face.”

“Hunh . . . ?” This was a piece of cultural awareness of which I had remained innocent. “What’s The Face?”

Ma shoved out her bottom lip. She scowled like a temple gargoyle and growled like a riled Pekingese dog, and I couldn’t help myself. For the first time since that locust swarm descended on our house to criticize Lily’s cooking and snicker at the bumbling American, I laughed. I laughed hard, and kept laughing until I was snuffling snot and blinking hot salt water, and then I looked at her presentation of The Face again, and bent over holding my gut and laughed some more.

Lily had gone and left me with her befuddled family and I was an ogre and Ma was modeling The Face like a Chinese opera fright mask and it was the best, funniest joke ever, or at least the best all day.

Ma’s eyes got big. She pulled her head back like a startled cat, cocked it over to the side and looked at me funny until finally she laughed, too. I wanted to hug her then, but I hadn’t earned it yet.

So we went into the light-filled kitchen of that low-mileage house, and I cut up fruit while Ma figured out the cupboard plan and found some pots and staples and spices (“Why you no have . . . what you call it?”), and we fed everyone into caloric oblivion until Lily returned the next evening, hard-eyed and silent, and the honeymoon with her family was over. It was a couple of years before I got up the nerve to ask her where she went that day.

And night.

My jet-setting, sleek corporate wife chuckled expansively then, answering that she’d rented a Mustang and driven on up to Vancouver, British Columbia to spend the night at a hotel. She let me know it was my fault (as if there had ever been any doubt of that). There were no further details and given her snarling, hair-trigger jealousy, I didn’t think to ask. I never do. Probably I don’t learn much that way. Maybe I don’t want to know much. Maybe I already know more than I want to.

Ma and I achieved some understanding after that day. She didn’t speak English comfortably and I had about five words of Chinese that I could recognize in Seattle and maybe a hundred when immersed in Houston’s Chinese community, but it was hardly an obstacle. We saw eye to eye on the bigger issues.

I habitually toted a sack of tools south when we visited Ma so I could kick-start the balky attic furnace, patch the roof, replace her hot water heater or just screw in a few light bulbs that had gone untended since her husband was laid out in state at the hospice, desiccated like a Pringle but still pulling breath while my wife moistened his lips with a soft cloth and her older sister enforced round after round of chanting, bejeweled, Buddhist ritual prayer.

I prayed for him to go ahead and die. By that point cancer and chemo had combined to immolate his body away like a soft wax candle, leaving Mr. Shui looking like a concentration camp internee who escaped by shambling blindly through the roaring ovens.

Because Ma was a wheel in the Chinese community there, ensconced into a weekly educational TV gig and beloved of Houston’s successive mayoralties, her husband’s demise would by necessity conjure a veritable pageant of squawking horns, flowing red silk banners and gilded dragons. After that, it fell to me to fix up the house.

What else was I going to do? I was gwai loh, foreign devil, Round Eye. I was the honky edition of “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” Friends of the family would come to stare when I was visiting, check me out from the corners of their eyes and chatter cheerfully in front of my back. I could either sit there staring at the big screen and pretend they were talking sports, or get up and grab a hammer. But I could fix up her decaying Eighties tract house, and Ma could fix supper like nobody’s business, and — pale hair or not — it wasn’t like she was likely to have another son-in-law to cook for anytime soon.

My sister-in-law was firmly betrothed to the seven rescue dogs fenced into various stench-pillowed corners of her tiny condo. There would never be a dowry big enough for Wen, but at least we built her a fence on one of our in-law shuttle diplomacy junkets. Then Ma cooked me one of her dinners that couldn’t be beat.

“She never cooks like that for anyone else,” my wife said with a strange little smile. “I guess you must rate.”

Then my sweet little thang marched back into the living room to pick another screaming fight in Mandarin, and I went back to hoovering my plate. Eventually — per routine and in the interest of securing the shredded remains of domestic tranquility — I dragged her gently out, grabbed our stuff from the guest room and threw it into a cab to head for the Red Lion Inn.

That was back in the sane times. That was before I trotted off to war, or put a nine-millimeter to my skull just to feel the brain-cooling muzzle steel as I eased on pressure until I felt the gentle break of my Glock’s trigger safety and relief rushed toward me out of the darkness like a midnight train, before Ma was committed for her own protection, before Lily went to a Wyoming spread to spend Thanksgiving with a boyfriend whose name I never learned and never will. One might even call them the good times, if one hadn’t seen better.

In Houston, I wasn’t allowed to talk to the doctors.

Lily’s sister Wen took care of that, bustling officiously around the nuthatch when she wasn’t demanding provisioning runs to PetSmart in my M&M-shaped rental car. I stood there, hands behind my back; physically hard, mentally vacant, waiting for instructions. Doctors and nurses and orderlies provided plenty of those.

“What does she need, Doc?” How high?

“She needs to get up and walk, as much as possible. She can’t just sit on her bed all day.” You better GIT yo’ raggedy ass in GEAR, soldier! Move! MOVE!

Ma didn’t want to get up. She didn’t want to put on her slippers. She complained that her bandages were too tight, tried to unwrap each bruised, lacerated arm with the opposing steel-cloven extremity. She was dizzy. She pushed away her meds with frail determination.

On a break outside in the sweaty Houston sunshine, I called my own Mom.

“I don’t even know what I’m doing here.”

“Why isn’t Lily there?”

“She has to work.”

“Don’t you think you should be taking care of your… wife?”

“Jesus, I don’t know. I cancelled my appointments with Casey.”

“Your VA counselor?”

“Yeah. And I missed a visit with Malia.”

“Jack, you need to take care of yourself first.”

“I’m okay!”

“Sure you are.” Mom paused a moment. “Then your daughter. Then your wife. Then other people.”

“Yeah, you’re such a good example.”

She laughed a little, and sighed. “You can’t be a doormat.”

I cleared my throat. Mom laughed again, only just a little, and said, “Very funny.

“Tell her you love her, then go home, Jack.

“Go home.”

“I don’t even know where that is, Mom.

“Love you bunches.”

“I love you, too, dear. Do what you need to do.

“Then go home. Promise me.”

“Bye, Mom. Love you.”

What I needed to do, according to the doctors, was get that trooper moving. It was time to be a sergeant again.

So up I went to the tenth floor, back through the triple security doors where they checked my ID just as if I hadn’t been there twice a day for the past three days, and zagged left down the hall to Ma’s room.

She shared quarters with a fat, grey-blonde woman who sat on the back bunk, too despondent to knot her pink terry bathrobe closed over the juddering, blue-veined colossi cascading sloppily over her cask-shaped belly. Whenever I walked into their room, she would squint intently at me from within the petulant folds of her purple-skinned face until I looked her way, then quickly become dramatically and huffily offended at my insolent invasion of her ladylike privacy.

There are few enough amusements in the booby hatch, I suppose.

Ma, for her part, sat over in the corner, practicing escape and evasion tactics to avoid the spoon zeroing in on her mouth. I took over from the orderly, and Ma looked at me gratefully until she realized that I, too, would try to feed her.

“C’mon, Ma. This stuff’s better than what KBR fed us.”

“I don’t like. My cooking better. Miss my own cooking.”

“Me, too, Ma! Me, too. So how about you eat some of this… uh, whatever it is… and then we’ll take a walk, and pretty soon we’ll get you home so you can make a big pot of your beef noodle soup.”

She looked at me and the glaze came off her eyes for a moment. “You li’e my beef noodle.”

“Yeah, Ma. I sure do.”

The overcast greyed out her eyes again, and she looked down through the floor. From where she sat, I was pretty sure she could see all the way to Hell.

“I hate this place. Hate my life.” She looked at me with something like the opposite of The Face. “Hate everything.”

“Ah, Ma, don’t say that.” Who’re you fuckin’ kidding, HE-ro?

“Where is Shui Li?”

“I told you before, Ma, remember? She couldn’t come this time.”

“Where Li-li?!”

“Ah, Ma, you know she’ll come through. We have to trust her, huh?”

I stroked her hair, waiting for the meds to kick in so I could feed her a little.

After a few bites of something like mashed pears, Ma started averting her head with birdlike quickness. By the time I had to dab her face with a cloth after each near-miss, we were ready to take our little walk.

When I slipped fuzzy bunnies over her swollen feet, Ma gave me The Face with an exponent and feebly kicked me in the eye. I couldn’t blame her for that — it wasn’t the Middle East and she didn’t mean anything by it — so I ignored her toe shot and put one hand on her closest biceps, well above the tattered elbow, and wrapped my other arm gently around her shoulders.

Ma and I carefully stepped out to pad up and down the main hallway, very slowly and nowhere near the secured, alarmed triple doors. According to our pattern, we would continue until she got too testy and desperate to continue our little march.

There was a lean, muscled young man on that ward. Once set in motion (yes, Drill Sergeant!), he shuffled unaided up and down our shared venue, regular as a metronome, never pausing or questioning his routine.

While Ma leaned on my elbow, the lad leaned on the adjustable steel tubing of the IV stand that was steadily dripping balance back into his life. With a white-knuckled grip from his big, red fist, he battened onto that stand like it was a wheeled shepherd’s crook.

Slowly, he advanced his left foot, then hesitantly brought the right foot even, then repeated the process. With painful deliberation, looking neither left nor right (if you needed peripheral vision, we’d’ve ISSUED you some), he measured out his testudineous cadence hour after lonely hour. High blood pressure and elbow bandages be damned, my 78 year-old mother-in-law was flat kicking his ass in these little wind sprints.

He consistently stepped out first with his left foot. That’s a military march habit, so I looked again and saw him. Despite his vacant stare, he wore his cornflower-embellished, butt-crack hospital gown with regimental posture. His brushy blonde hair was trimmed flat on the top, shaved high and tight up the sides.

There wasn’t enough gown fabric to cover his arms, peculiarly hypertrophic in the instantly recognizable fashion of those who have performed way too many pushups. Still vibrantly saturated and crisply lined, the bullet-torn flag coloring his thick biceps hadn’t flown there long. I wondered which post town had supplied the artist: Fayetteville, North Carolina? Tillicum, Washington? Killeen, Texas?

I wondered where he’d lost it, gone off the reservation, disconnected himself from the unthinkable by some unthinkable act: Fallujah in al Anbar, Iraq? Bagram, Afghanistan? Killeen, Texas…?

All through the darkening hours after Ma went on strike from walking to sit disconsolate on her bed, that soldier pushed his IV rack up and down the sodium-lit, gray-waxed, speckled tiles of the loony bin hallway. Yo’ lef’, yo’ lef’, yo’ lef’-right-LEYUF!

Sitting in the plastic chair just inside Ma’s door, I wondered who to call next. I wondered when my flight left, and where it would land.

Dressed in my split-hide desert boots and a Calloway golf shirt, I sat there for a long time and listened to his IV stand squeak up and down, up and down, up and down. The squeak got louder each time he approached her door, then diminished in a predictable, slo-mo Doppler fade as he passed, the wobbling chrome support giving him one last, tangible thing to hold onto in the night.

Wondering who would come for him, who would saddle up and make the time and prove to all of us that no soldier will be left behind, I went and stood in the door. I watched him walk past, one dragging step at a time, and as he came even with the door I stood to attention and saluted him, never making eye contact, looking straight ahead. He never broke stride, or glanced sideways into that sad little room. He kept going, straight on into the night.

But three slow steps past the door, the broken soldier halted. The dirge-paced squeaking stopped for the first time that day. Soundlessly, he took his big, sunburned hand off that IV stand and raised it up in a small wave. I wanted someone to hug him, but it couldn’t be me so I turned toward the ward doors (column right, MARCH!) and left the hospital (double time, MARCH!) with my Face screwed firmly into place.

Outside, I phoned no one. I didn’t hail a cab or catch a train but speed-marched away down the sidewalk, digging in my boot heels. After the first few steps I broke into double-time, counting my breaths, measuring my pace.

Indistinguishable from bayou humidity or rain or tears, sweat rolled down to hide safe in my desert boots as I ran on and on, straight into the night and free, maybe, going home or anyway somewhere.

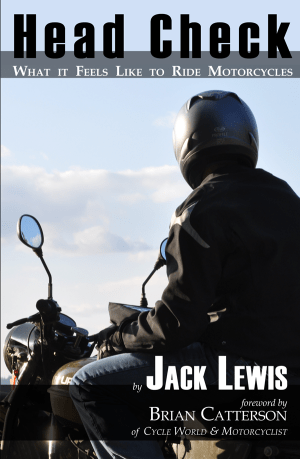

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Jack Lewis takes the overall literary crown with his new book...there’s a lot more to Lewis’s work than what it feels like to ride motorcycles.” — Ultimate Motorcycling

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

"Insightful and from the heart ... a driven and much recommended look into the mind and conflict of the next generation of war veterans. " — Midwest Book Review (Reviewer's Choice)

I’ve never worn the Uniform. I haven’t Been There and Done That. But somehow I grok it anyway… not in fullness as you do, but I *get it*….

Well enough to know that writing that had to hurt.

One of those things that, like praying to the porcelain god, feels better when it’s done… but that had to hurt.

Thanks for sharing, my friend. And now that you’ve got that off your chest… go enjoy yourself. As shall I. Part of me wishes we were going the same place… but. *private smile* I hope the story you have to tell when you get back is a helluva lot happier.

You earned it, trooper. The hard way.